Ruben Lundgren: Dream Machine

We can only imagine how mind-blowing it would have been to have witnessed the arrival of the first ever automobiles in China. Over a century ago, city folk and ordinary farmers must have stopped whatever they were doing to admire the mysterious vehicle which moved seemingly without human effort. Some said it was driven by ‘evil spirits’. But then, they had said the same about the invention of the camera and its magic mirror years before. Others, with a slightly better sense of humour, called it a ‘foreign house walking’, or even wittier, a ‘fart cart’, for the black smoke that invariably dissolved into the air behind it.

It’s a common mistake however to believe that by the early 1900s, the Chinese population was hostile towards foreign products or modernity. Generally speaking, they enthusiastically embraced new trends that were then pragmatically woven into the fabric of everyday life. Luxury imports were used by elites as visual evidence of social status, while cheap imitations satisfied the demand for new products among ordinary people: both were absorbed into a culture that without the tangible and craved the new. [1]

In Hangzhou for example, large crowds at the West Lake marvelled at photographic slide shows demonstrating that ‘the eyes can take the audience to many places’. By the 1930s, the city had dozens of photographers. Ordinary people could have their portrait taken in black and white while those with more cash had theirs painstakingly tinted by hand. Inside the photo studio, efforts were made to recreate a modern atmosphere with painted landscape backgrounds and foregrounds of the latest machinery in fashion. From the first motorcycles in the 1940s, to tanks in the 1950s, planes in the 1960s and televisions in the 1980s, the eagerness for new technology has proven to be a continuous cultural habit that can still be felt today.

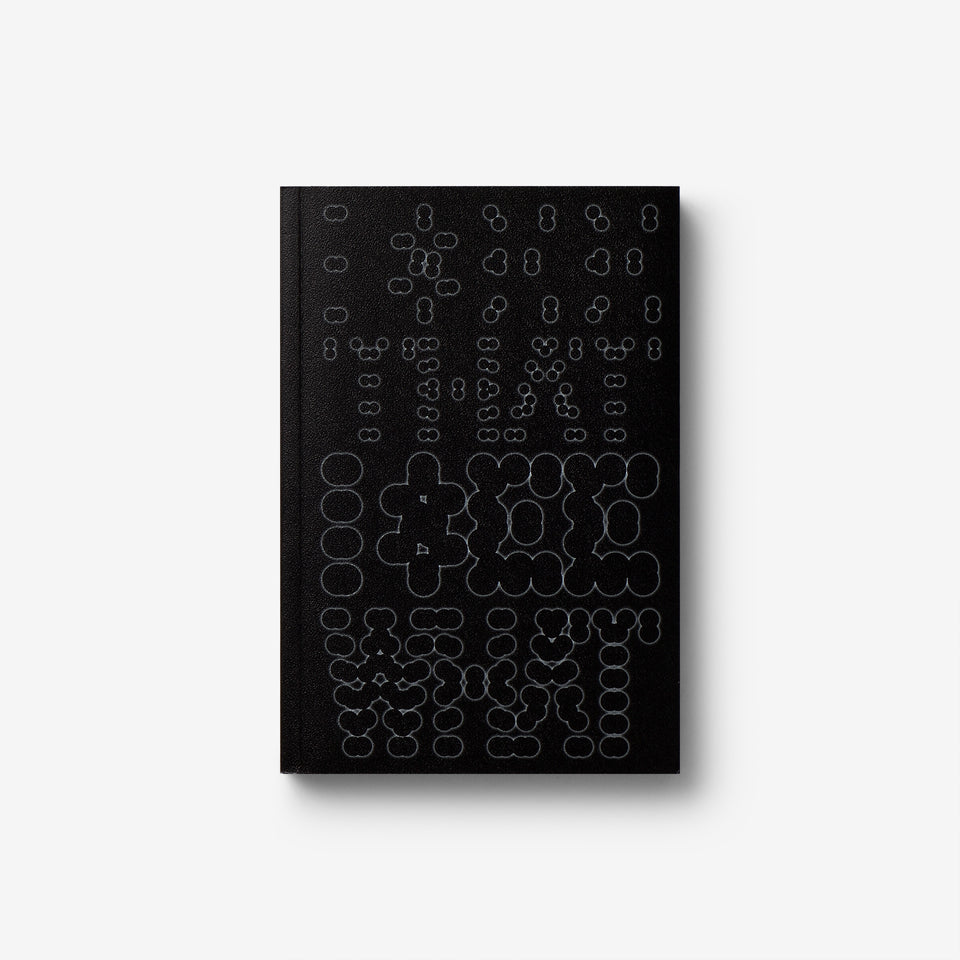

This album consists of 35 photographs I collected at antique markets and via websites in China over the past decade. The colourful graphics are copied from an album originally produced in the 1960s which offers a historical tour along the banks of the famous West Lake. The portraits capture the futuristic appeal that machines like cars, planes or televisions once had. Like the invention of the internet, smartphone or e-bike in recent decades, most innovations slowly slip away into the common present.

[1] Frank Dikötter, Exotic Commodities, Modern Objects and Everyday Life in China, Columbia University Press, New York, 2006

Beijing based photographer and curator Ruben Lundgren graduated from China Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2011. He made a name within the conceptual photography duo WassinkLundgren with publications as ‘Empty Bottles’ (2007) and ‘Tokyo Tokyo’ (2010). FOAM showed a retrospect of their work in 2013. He works as a photojournalist for Dutch newspaper ‘De Volkskrant’ and as an independent curator of Chinese photography. Together with Martin Parr he co-edited ‘The Chinese Photobook’ (2015). Other publications include ‘Hlleo?’ (2018) and ‘MeNu’ (2018) a tasty collection of Chinese vernacular food photography. As a guest curator of BredaPhoto 2020 he curated ‘China Imagined’ offering 24 contemporary photography projects from China including the sticker album ‘Wow Taobao’. In 2021 he edited the book Ellen Thorbecke: From Peking to Paris, and published Real Dreams with his journalistic works made all over China. His photographs and books are collected by various private and public collections and have also been exhibited at international galleries and museums including FOAM photography museum (Amsterdam), The Archive of Modern Conflict (London) and Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art (Beijing).

Pages: 68

Dimensions: 180 × 255 mm

Format: Hardcover

Language: English, Chinese

Year: 2023

Publisher: Jiazazhi